Bob Graham (Phillips Holmes) is one of those inmates. He was sent up the river by Brady, and when Brady is named warden of the prison where Graham is serving his time, their paths cross again, as do the paths of Graham and Brady's daughter, Mary (Constance Cummings).

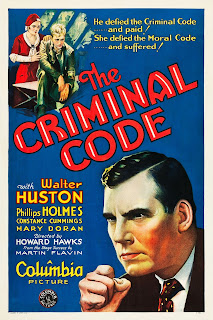

The 1931 film, directed by Howard Hawks, has an Oscar-nominated screenplay by Seton I. Miller and Fred Niblo, Jr. And it's a much bleaker view of prison life, with morally dicey characters to match, than its 1950 remake, "Convicted." (Miller and Niblo are also credited with the screenplay of "Convicted," along with William Bowers.)

In "Convicted," Broderick Crawford is the D.A.-turned-warden, here named George Knowland. And Glenn Ford is the inmate, here named Joe Hufford. Dorothy Malone plays Knowland's daughter, Kay, even though in real life Crawford was only 14 years older than Malone.

The characters of Brady and Knowland are similar on the surface -- assured, self-made men who believe in the system and in the sanctity of the law. But Brady has rougher edges -- he smokes stogies as opposed to Knowland, who prefers a more professorial pipe. And Brady is a bit of a politician -- he is given the warden's job as consolation for a losing race for governor, and he's always worried how things will look to his enemies. By contrast, Knowland is more able to see life's gray areas, if just barely.

The movie begins with a death -- the son of a prominent political figure has been killed by accident in a nightclub fight. The character played by Holmes and Ford -- we'll call him Bob/Joe -- is the "killer," although both prosecutors know that the act was accidental and in self-defense.

"Tough luck, Bob," Brady tells Bob in the 1931 film, "but that's the way things go ... you gotta take 'em the way they fall."

But Bob doesn't have to take 'em that way, and Brady knows it -- but he doesn't tell Bob.

"If that kid belonged to me," Brady tells his assistant (and no one else), "I'd make a plea of self-defense and fight it out. I'd get him out ... he'd never serve a day. A thing like this is liable to happen to anyone."

Brady is content to "let things fall" and let Bob face the music. Bob's counsel is just this side of incompetent -- he's a corporate attorney, hired by the brokerage house Bob works for, who knows nothing about criminal law. And Brady offers no guidance whatsoever.

In the 1950 film, Knowland at least advises Joe's attorney to hire a criminal lawyer. But it's for naught.

As expected, Bob/Joe is convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to 10 years in prison. In the 1931 film, Brady stands stoically by as the sentence is passed and a bailiff picks his teeth. Bob's useless attorney blows off the whole thing with a simple "the best man won, I'm afraid" as Bob is taken away to the big house. In the 1950 film, Knowland at least shows some pangs of conscience -- he tells off Joe's lousy lawyer -- and his humanity is further emphasized by having daughter Kay with him, noting his sadness:

Despite all that, Bob/Joe's best friends are his cellmates, and between them they illustrate that other criminal code -- the one that isn't in the law books.

Bob has been in prison, wasting away, for six years before Brady becomes warden; in the 1950 film, Joe has only been in for three years before Knowland's arrival. Because Brady/Knowland is responsible for putting so many of the inmates behind bars, they greet his arrival with "yammering" -- a long, loud series of growls. Both men decide that the only way to deal with the uprising in the prison yard is to confront the yammerers:

Meanwhile, Bob has been falling apart in prison. He works every day in the prison's dirty, dusty jute mill, spinning fiber into burlap. Then he receives word that his only contact with the outside world -- his mother -- has died. This leads to a breakdown in the jute mill and, after a doctor's intervention, Brady appoints Bob as his chauffeur.

In "Convicted," Joe is close to his father. and while he's in stir, Kay visits the old guy, creating a bond between she and Joe even before they meet. As opposed to Bob's stint in the jute mill, Joe works in the prison laundry -- not a perfect setting, but at least it's cleaner. Joe's breakdown occurs when he learns of his father's death, and as a result he's put into solitary -- it isn't until he's released from there that he joins Knowland's staff as chauffeur.

Still, Joe's time in solitary doesn't seem to affect him as much as Bob's. In general, in fact, Holmes looks like hell for a good part of this movie, while Ford looks like ... Ford.

Still, Joe's time in solitary doesn't seem to affect him as much as Bob's. In general, in fact, Holmes looks like hell for a good part of this movie, while Ford looks like ... Ford.As the prison chauffeur, Bob/Joe spends more time driving around the warden's daughter than he does the warden himself. And things start improving as prisoner and daughter are drawn to each other.

Then comes a crisis, one involving both of Bob/Joe's cellmates. One attempts to escape, only to be shot and killed because one of his co-conspirators was a stool pigeon. The other cellmate -- the one determined to kill the yard warden -- also sets his sights on the stoolie.

Warden Brady/Knowland is hiding the stoolie in his office.

"I gotta get him off my hands," Brady says to the head of the parole board. "Pardoned, paroled transferred -- anything!" So he has no hesitation about letting the guy go. Knowland is more principled -- he wants the guy transferred, but not set free.

|

| This guy doesn't need Frankenstein makeup. |

It falls to the warden's daughter to set her father straight:

Bob/Joe is released from solitary and paroled, and the "happy" ending fits each film's tone -- Brady looks a little uneasy at the idea of his daughter marrying a convict, even a noble one; and Knowland and Joe joke about his picking up the daughter as nonchalantly as if it was a Saturday night date.

No comments:

Post a Comment